Thechniques for Refinishing Plaster Framesdeer Skull and Antler Art

Conservator examines a Chinese vessel.

Conservation-restoration of bone, horn, and antler objects involves the processes by which the deterioration of objects either containing or made from bone, horn, and antler is contained and prevented. Their utilise has been documented throughout history in many societal groups every bit these materials are durable, plentiful, versatile, and naturally occurring/replenishing.

While all three materials have historically been used in the cosmos of tools, formalism objects, instruments, and decorative objects, their individual compositions differ slightly, thus affecting their care. Bone is porous, every bit information technology is a mineralized connective tissue composed of calcium, phosphorus, fluoride, and ossein, a protein. Horn consists of a keratin sheath over a bony outgrowth, as seen with cows and other animals. Antlers are a reoccurring bony growth on the skulls of male person members of the deer family (apart from reindeer/caribou, in which both males and females produce antlers.) Unlike horn, which is a permanent feature, antlers are typically shed and regrown each year.

While these materials have a well-documented by as sturdy and reliable choices for tools, ornamentation, ceremonial objects, and more than, they are organic materials that deteriorate if not treated properly. Deterioration may occur if objects made from these materials are subjected to farthermost oestrus, dryness, wet, or a combination of rut and moisture due to their highly porous nature. Other sources of deterioration include pests, acids, and overexposure to light. Information technology is highly recommended that a conservator be contacted if a museum has bone, horn, or antler objects in need of conservation, as many adhesives, liquid cleaners, and protective coatings may irreversibly harm the object.

Identification and composition [edit]

Many museums contain objects in their collection that are made of bone, antler or horn. Ane of the about important steps in the conservation of these objects is determining which material it is.

Tibia - detail of bone tissue (proximal end).

Os [edit]

Os, which has a very similar chemical make-upwards to ivory, consists of inorganic materials which provide strength and rigidity and organic components that provide the capacity for growth and repair. Different ivory, which has no marrow or blood vessel arrangement, bone has a spongy central portion of marrow from which extend tiny blood vessels; os is therefore highly porous. Os is also made of both mineral and carbon-based materials; the mineral-based are calcium, phosphorus, and fluoride; the carbon-based is the protein ossein. Bone besides includes the mineral hydroxyapatite, "A calcium phosphate mineral which forms a hard outer covering over the collagen and poly peptide matrix,"[i] or organic material.

Bone housed in museum collections come from many different sources; mammals, fish, birds, and in rare cases humans may all be included in a museum's drove. Bones in these collections tin can come up in many shapes and sizes. It can be used in its natural form or polished with sand and other abrasives to create a smooth, glossy surface. It may as well undergo a burning process, which gives information technology a blueish-black to whitish-grayness color.

Bones of all kinds have been used to create many different objects throughout history, from tools such as hammers and fishhooks to weapons such as spears, arrows, and harpoon points, or other items, such as pendants, hairpins, gaming pieces, musical instruments, and ceremonial objects.

Rustic deer antler candle holder.

Antler [edit]

Antler, a modified form of bone, grows out of the skull basic of certain species of animals, such as deer, and is typically shed in one case a year. It consists of a thick layer of meaty os, an inner section of spongy bone, and internal blood vessels that are less and more irregular than the ones present in bone. Antler is denser and heavier than skeletal bone and differs from skeletal bone in its external appearance. Skeletal os is usually smooth except for areas of attachment to muscles, tendons, and ligaments, while antler generally has raised bumps and protrusions across the surface.

Similarly to bone, antler may be used in its natural grade, polished with abrasives for a glossy surface, and treated with a burning procedure for a charred end and colour. Antler has been used for numerous objects throughout history including tools such as hammer batons, pocketknife handles, pressure flakers, and conical pointer points.

The Bruce Horn or Savernake Horn.

Horn [edit]

Horn is the outer roofing of a bony outgrowth on an animal's skull, such every bit a cow. It consists of a mass of very hard, hair-like filaments called keratin, cemented together around a spongy internal os core. This layering effect continues to abound over time, resulting in a cone-within-cone structure. Unlike antlers, horns are permanent and not seasonally shed. Another distinguishing cistron from bone and antler is the fine parallel lines that are present on the surface of the horn. Horn comes in a great variety of sizes and colors, including white, green, cerise, dark-brown, and blackness.

Horn can exist used in its natural state, boiled, cutting, molded to other shapes, or used in flat sheets. It has been used for a variety of objects including ceremonial decorations, utensils such as spoons and containers, gaming pieces, and combs.

Carved ivory horn, National Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh.

Ivory [edit]

Many mammals, such equally elephants, walrus, narwhals, whales, and hippopotami, produce tusks and teeth of ivory that tin be used for etching; these are the most ordinarily found ornamental ivory objects in collections today. As mentioned above, ivory is very similar to bone in its chemical brand-upward. Like os, it is composite, consisting of both organic and inorganic materials that at once allow for its rigid surface as well as its capacity for growth. However, while the chemical compositions are similar, the physical construction of bone and ivory are very dissimilar. For example, "ivory is dentine--the part of the molar that is covered by enamel."[ane] Ivory is tooth material, pregnant "it is usually whiter, harder, denser, and heavier than os,"[2] which has a spongy central portion that ivory does not. Moreover, "ivory, which has multiple layers, is more dense than bone or antler and is more than likely to crack or delaminate while drying."[three]

Identifying the type of ivory you are working with can exist done by examining the intersecting patterns that cross the surface of the ivory. Elephant ivory, for instance, volition showroom a design of intersecting arcs called schreger lines, that hatch across the surface at 115-degree angles.[four]

Examples of ivory objects include: horns, handles and inlays for ceremonial weaponry, jewelry, and decorative arts; statuettes, regalia masks, and even triptychs.

Agents of deterioration [edit]

Fire at the National Museum of Brazil, in Rio de Janeiro, on September 2, 2018

The term agent of deterioration is used to identify the major activities, natural and human being-made, that threaten a museum collection.[5] A key preventative measure in conservation is surveying the environment and making a take chances cess of the biggest threats to the drove. The environment ranges from the storage container, storage room, the building, what is outside the edifice, the surrounding businesses and mural, the climate and geography, and the year round weather changes.

Physical forces [edit]

Physical forces that tin damage a collection are the vibration, stupor, gravity, and abrasion that can be gradual over fourth dimension or sudden and catastrophic.[5] This tin be from an convulsion, being dropped, or stress of compression from the general weight of the object.

The most common physical forces on bone, antler, and horn are mishandling, over handling, beingness dropped, or being unbalanced while on display or in storage causing stress pinch on weak spots. Sweat and oils left backside bare hands assist in promoting mold growth and other damage to the objects. Wearing gloves, handling the object with two hands (rather than i), and avoiding any weak spots on an object will help foreclose harm.

Fire [edit]

Fire tin completely destroy the object. Fires are not common, simply they are highly subversive. Heat from a nearby fire tin cause objects to go brittle or crack, and cause its destruction. Fume tin can stain the object. Damage from fire is irreversible. Objects that are fabricated of organic materials are "highly susceptible to combustion, particularly if very dry."[6] The smoke harm can come from a burn "both within and outside of the museum."[5]

Water [edit]

Water tin come up from roofs leaking during rainstorms, floods, burn sprinkler systems, or broken pipes.[7] Information technology can soften and destroy the bone, antler, or horn if information technology becomes waterlogged. Mold and mildew growth can crusade further damage. If the water in the crevices or pores of the os, antler, or horn were to freeze, information technology would crack the object.

Criminal offence [edit]

Theft and vandalism are everywhere, therefore, keeping the objects in locked display cases or locked storage while using surveillance cameras in the gallery and limiting personnel in collections is the nearly preventative measures.[8]

Pests [edit]

Pests are a "living organism that are able to disfigure, damage, and destroy material civilisation.[9] Dermestid beetles, silverfish, and rodents are mutual pests in museums. There are "beneficial" pests, similar spiders and centipedes that feed on harmful pests. Past knowing what blazon of pest, their beliefs, and preferred habitat, the pests can be controlled. If there are beneficial pests, then at that place are harmful pests. Disrupt the habitat of the harmful pest and both volition become away.

"Once established, populations tin more hands motion on to collections storage spaces and other relatively fortified nonpublic spaces."[x] Pests like to snack on organic matter and cause damage to the object. Trap and monitor systems tin can identify what pest is present while learning about the habits of that pest tin can tell you lot how to go rid of it; it may be the temperature that was welcoming.

Lite, ultraviolet and infrared [edit]

"Light, by definition, is the band of radiation to which our eye is sensitive."[eleven] On the ends of this light spectrum (measured in wavelengths) are ultraviolet radiation and infrared radiation that are non visible to the homo eye, but tin can exist very damaging to objects. In museums, filtered lighting with a shorter spectrum that excludes as much ultraviolet and infrared as possible is used to reduce the impairment information technology causes.

Organic materials are highly sensitive to lite and the light volition cause fading or structural damage if it is not filtered and kept low.

Temperature, relative humidity and pollutants [edit]

Temperature that is too high, too low, or fluctuates in a large range causes materials to become brittle, delicate, or deteriorate through chemical methods such as acrid hydrolysis. Relative humidity (RH) is the measure of "humidity" that we perceive in ranges from dry out to clammy.[12] Information technology is read as the pct of moisture in the air. Pollutants are the compounds that can crusade chemic reactions to object materials. Pollutants include gases, aerosols, machine exhaust, emissions from nearby factories or structure work, fifty-fifty the off-gassing of volatile organic compounds from other museum objects.[13]

A filtered air-conditioned storage surface area can control the temperature and relative humidity while simultaneously circulating the air which removes pollutants and prevents mold growth[14] while creating an uninviting environment for pests. A relative humidity level that is too low (dry, below xxx%) with crusade the bone, antler, or horn to crack; too high (clammy, over 75%) and they are subject to expansion and mold growth that can atomize or discolor. Fluctuations over 3% within a 24 hour period can cause objects to not bad and contract, weakening the material and causing harm.[15]

Disassociation and custodial neglect [edit]

Dissociation and custodial neglect are the lack of protective treat an object or collection. This ranges from physically misplacing an item, improper storage or brandish, and lack of cleaning the object and surrounding expanse that increase the likelihood of the in a higher place mentioned agents of deterioration. "Without vigilant housekeeping, a sufficient amount of droppings tin easily accumulate in public spaces to support breeding populations"[10] of pests.

Preventive conservation [edit]

"Preventive conservation is the most effective method of preservation. The goals are to provide a stable and protective environment and to avert those conditions that accelerate deterioration."[xvi] This is particularly true of collections pertaining to or consisting of organic materials.

Storage and handling [edit]

Archival boxes in museum storage

Like any museum objects, the treatment of bone, antler, and horn should exist conducted in a manner conducive to maintaining the health of the object. While these objects may be handled with clean, dry out hands, body oils can stain their surface due to the porosity of these materials. This is especially noticeable on light-colored antler, horn, and bone. Wearing cotton or latex gloves tin preclude the spread of harmful oils to these objects.

Items that contain os, antler, or horn should always exist lifted and moved in a fashion that is fully supportive and does not place unnecessary stress on weak areas or attachment points; using an acid-free tray is highly recommended.[17] These objects can be protected further by being wrapped in unbuffered, acid-gratis tissue newspaper and/or placed in a sealed polyethylene purse when being transported.[2] Bone, antler, and horn objects are stored in tightly closed display cases or drawers to buffer them from sudden changes in temperature and relative humidity while shielding them from dust and clay. By storing them in the dark, these lite-sensitive materials that are dyed or painted are protected. To preclude bumping and chipping, the storage drawers and shelves are lined with a chemically stable cushioning material such as polyethylene or polypropylene sheeting, equally opposed to a safe-based fabric that can produce unnatural yellowing.[2] Items with holes, straps, appendages, etc. are never hung or supported by said attachments. Instead, they are stored with a back up at the base of operations of the particular, and a back up for the natural position of the handle or strap.[17]

Proper storage also aids in the regulation of temperature, relative humidity, and rubber illumination levels, which can have disastrous effects on these organic materials if they fluctuate.

Humidity [edit]

Humidity tin can prove extremely unsafe to bone, antler, and horn objects, their organic limerick makes them especially decumbent to ecology fluctuations and unstable relative humidity, or RH levels can cause irreversible impairment in your collection.

Relative humidity should exist controlled to the extent your facility is capable, and fluctuations should be minimized every bit much every bit possible to prevent these potential damages. "The specific RH fix points for a collection will vary depending co-ordinate to climatic considerations, the facility'south control capability, the condition of the objects in the collection, the requirements of the textile and composition, and the equilibrium moisture content to which the objects are accustomed."[16] The following are recommended levels for organic collections:

- Relative humidity is kept at a level between xxx percent (in the winter) and 55 percent (in the summer) with fluctuations of no more 15 pct during each flavour.[17]

- Mold can infest these organic objects when the relative humidity in storage and display areas exceeds 60 percentage for extended periods of time. White or green fuzzy growth on the surface of these objects is an indicator of a mold infestation. Expert ventilation and air circulation prevents mold as well as properly regulating relative humidity levels.[17]

Avoiding excessive heat [edit]

Changes in temperature, such every bit excessive heat, can destabilize relative humidity levels, which can result in a myriad of conservation issues for organic objects such as embrittlement. A few examples of oestrus sources that tin can damage museum objects, and organic materials, in particular, are showroom lighting, direct sunlight, and their position in relation to heat registers, and radiators.[16] In society to circumvent excessive heating of objects, these common sources should exist avoided and temperatures should be kept every bit constant as possible, no greater than 68 degrees Fahrenheit with no fluctuations of more than +/- 3 degrees a 24-hour interval.[17]

Atmospheric pollutants [edit]

Museum objects require a specific environment. Just as people need air to breathe, objects need air that is free of contaminants and pollution. Unfortunately, in a museum, these ii things cannot always be mutually exclusive. People must exhale air and the air often has pollutants in it that tin can exist damaging to the objects in a drove. Industrial areas, construction, heating systems, and even visitors often contribute to this problem. Luckily these tin can—and should be—eliminated from an object'southward environment where possible.

Pollutants can be divided into two main categories:

- Gaseous

- Oxidizing

- "The process involves the germination of free radicals, acids, and other compounds in many materials,"[18] they are particularly damaging to organic materials, causing them to get more breakable.

- Acidic

- "Acidic substances such as sulphuric acid and nitric acid are corrosive because they readily react with many materials and crusade permanent changes."[18]

- Oxidizing

- Particulate

- Particles can be either large or pocket-sized, alkaline or even acidic. They are oftentimes abrasive and may scratch the surface of objects when they are being handled, or cleaned. Another consideration is that particles may create residue by settling onto the surface of objects.[xviii]

Pollutants such as these tin can damage the structural integrity of organic objects, making them weak, brittle, or fifty-fifty corroding the surface. That is why it is important to utilize preventive collections care measures wherever possible. The most effective method is to but prevent pollutants from entering the building itself, this tin can exist done by purchasing ac and filtering methods to filter the air, and properly ventilate the building. As an added safety measure you lot tin likewise implement a policy to minimize the opening of doors and windows, as well equally retrofitting seals and doing secondary glazing on glass.[xviii] Finally, pollutant absorbers, such as activated charcoal can be added to display cases, or fifty-fifty placed in storage areas to add another layer of protection.[16]

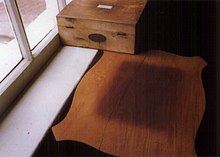

Light has faded the finish of the table top except in the centre, where the box rested and shielded the finish. The finish on the top and back of the box is nigh completely lost.

Light harm [edit]

Light impairment is cumulative and irreversible, it occurs when an object is exposed to lighting over an extended flow of time and is related to the intensity of the lighting. However, it is important to note that an object may see the same amount of lite damage if left exposed under low levels for 24 hours or left under intense showroom lighting for a shorter period of time.

Light can be divided into three categories: Ultraviolet, Visible Light, and Infrared.

- Ultraviolet: Daylight tin can be the strongest source of UV low-cal and every bit it is invisible to the human heart, tin can be difficult to go on from your museum setting. "The loftier energy of UV radiations is specially damaging to artifacts."[19]

- Visible low-cal: Visible low-cal is, of grade, necessary for museums. Visitors and staff have to be able to see the artifacts on display and without calorie-free, this would exist impossible. The standards that have evolved in the museum customs reflect this reality, light is necessary for the basic functions of a museum. Anything more than what is needed for bones functions can crusade unnecessary impairment and should be express.[19]

- Infrared: Infrared light can be particularly dangerous because like ultraviolet calorie-free it is invisible to the man eye, making it difficult to capture. Moreover, information technology causes a rise in temperature which tin can be harmful to many objects in organic collections. Bone, antler, horn, and ivory are susceptible to excessive estrus and temperature fluctuations.

Below are recommendations for ordinarily acceptable low-cal settings:

- Illumination is kept below 150 lux, with the ultraviolet (UV) component restricted to 75. Dyed objects are extremely calorie-free-sensitive and being exposed to lux levels more than 50 is dissentious. Maintaining low light levels while using lights that emit less radiant heat is an effective way to foreclose damage. Shining directly vivid lite on tightly sealed storage units can reproduce loftier temperatures and high RH internally, putting the stored objects at chance.[2]

Please annotation that "Any level of light in excess of the minimum amount necessary to adequately view an object on exhibition causes unjustifiable impairment."[19]

Integrated Pest Direction Natural History Museum London

Integrated pest management [edit]

The term Integrated Pest Management refers to the series of pest command and prevention methods that museum staff and collections intendance professionals apply in their efforts to ensure the prophylactic of their collections. Damage to collections is primarily acquired past the following pests: termites, bookworms, cockroaches, silverfish, booklice, carpet beetles, clothes moths, rodents, birds, and mold,[xx] the type of pest is often dependent on the type of collection. Os, antler, horn, and ivory are non particularly susceptible to insect damage, such as termites or booklice, and so long as the objects were properly prepared before existence added to the collections. However, they are vulnerable to insects and even plant growth, earlier proper cleaning. Pests, for instance, are attracted to the fatty, grease, or remaining tissues in, or on bone. Plant growth is a further concern, "Archaeological specimens are generally covered with clay and are often penetrated by the roots of pocket-size plants,"[21] upon initial discovery. Rodents are also a consideration for organic materials. Antlers, for case, are a groovy source of calcium and phosphorus for rodents, they tin can ingest these minerals just by gnawing on the antlers.[22]

Preventive measures such as maintaining skillful housekeeping, following an integrated pest management programme in storage and display areas, and employing regular pest control services will assistance prevent infestations.[17]

It is recommended that y'all create a pest management programme that takes all of the post-obit into consideration and work with pest direction professionals to ensure the continued safety of your collections, these tin can include only are not limited to:

- routes of pest entry into the building

- The building's construction, and whatsoever nuances that make pest entry easier

- exhibit design and construction

- The types of pests that may exist dangerous to specific collections

- types and amounts of pests found in the surface area, well-nigh the building

- Policies and procedures, storage practices, and general housekeeping that might easily introduce pests.[23]

Display mounts [edit]

Preventive care can protect bone, antler, horn, and ivory objects from damaging elements, but objects on display are put at risk and therefore need to exist carefully prepared likewise as monitored. The adoption of protective enclosures such equally exhibit cases with advisable temperature command tin can assist in "Minimizing relative humidity fluctuation, as well equally reducing handling, soil accumulation and infestation of microorganisms, insects, and rodents."[16] While the employ of external supports and mounts fabricated from safe materials in exhibit displays can also provide an added layer of protection for the object. Bone, antler, horn, and ivory objects tin be fastened to the mounts through the application of wires or apartment acrylic plastic clips. However, metals that come into direct contact with these organic objects tin can cause harm. The fats that may remain in these organic items react with metal, forming corrosion products that will stain the objects. For this reason, it is all-time to avert placing the wires in direct contact by padding them. The utilise of adhesive mounts should be avoided entirely.[v]

Rotating the bone, antler, horn, and ivory items on display, following a set timeline, prevents them from beingness exposed for extended periods, thus reducing the risk of all-encompassing lite damage.

Conservation science [edit]

IMA Conservation Scientific discipline Lab

Conservation science is a varied and complex field with aspects devoted to the report of objects' materials, uses and origins, how they degrade over time, and techniques for care, storage, and display. Antler, bone, and horn have been heavily used for tools and other objects for at least 1.five one thousand thousand years, and proceed to exist used today, though modern materials such as plastic and metal are now predominant.[24] Bone, antler, and horn create relatively durable items; long bones (femurs, phalanges, etc.) and antlers provide the near versatile working material for many tools, simply all parts of a skeleton tin can exist worked.[25] Horn has numerous applications, from medieval hornbooks to 19th-century hair ornaments and more than.

Examining signs of modifications to bones can offering conservation scientists information most age, usage, creative techniques, and previous attempts at conservation. Critically, conservation science allows scientists to make up one's mind if bone, antler, and horn remains were worked by humans or simply altered past the environment, which in plough leads to new discoveries of tool usage, peculiarly in early humans. To date, some of the earliest tool usages have been discovered through the analysis of wear patterns on os.[24] This is known as use-wear analysis, in which objects are microscopically examined for their wear patterns and striations. Such analysis determines if an object is a tool or was worked past humans and can also make up one's mind what an object was used for. Bone and antler tools, for example, volition begin to polish over time with repeated use. By examining the worn, polished areas, scientists may make up one's mind how a bone or antler tool was held and used.[26]

In add-on to determining what an object is and how it was likely used, conservation scientists effort to decide the object's likely age. In the by, this was washed with relative dating, in which the surrounding area of an object's discovery was examined, and the geologic stratigraphy used to settle upon the virtually likely historic period range. As this method was less than verbal, contemporary scientists prefer absolute dating, such as radiocarbon dating. Radiocarbon dating, also known as carbon dating, determines an object's historic period by isolating and measuring the level of radioactive carbon-14, as living things absorb and accumulate carbon naturally over their lifetime. Once an organism dies, carbon levels begin to drop and carbon-14, being an unstable isotope, slowly decays to carbon-12. Based on how much of the carbon-14 isotope remains in the object, scientists are able to determine an objective age. As bone, antler and horn are all derived from living organisms, determining the level of carbon-14 versus carbon-12 is considered quite effective and is the most widely used course of absolute dating.[27]

Treatment [edit]

Treatment is the intentional application of a restoration process to an object in need of care by a conservation professional. Reasons for treatments can vary, whether to repair significant impairment, to stabilize an object in poor condition, or to set up an object for exhibition. Whatever the reason it is important to notation that "Restorations--indeed all treatments--are cumulative. The preservation of objects in perpetuity implies that they will undergo treatments in the future as many accept already in the past. Thus in that location is an ethical imperative for minimizing treatment since subsequent intrusion moves the object farther from its original state."[28] This can be especially true of bone, antler, and horn, objects, already removed from their original environments. Bone, horn, and antler objects are often part of museum collections and are unique because they require special considerations in terms of care. For case, bone, being an organic material, if placed nether the correct atmospheric condition volition somewhen suspension downwards whether in nature or in the collections.[one] causing treatment to be necessary.

Cross section of ivory tusk. Exemplar in Victoria and Albert museum, London.

Determining material [edit]

Treatment methods may differ for each cloth, ivory for example is more than dense than bone and may scissure or delaminate while drying. Determining the type of material is necessary to decide the course of treatment. Before treating an object a status assessment is completed to ascertain what condition the object is in before deciding whether treatment is necessary and if so what class of action is all-time. The relative condition of bone tin can be tested in many cases, past compressing the surface of the textile. "One good indication of condition is the hardness of the surface… If information technology compresses or feels spongy, the material has deteriorated."[3]

Different objects, whether organic, composite, or inorganic, take different needs. Handling methods should be a reflection of those needs and carried out accordingly.

Stabilization, repair, and restoration [edit]

Once the condition of the object and what the issues facing the object have been determined a grade of handling is decided upon. "Any conservation activity should, therefore, follow sufficient research in order to identify the needs of the objects and safeguard their values and functions."[29] In other words, different objects have different needs and handling methods should be carried out appropriately. For example, consolidation is a treatment method that can strengthen an object that is weakened, simply information technology can as well interfere with chemical assay. Stains might exist able to exist removed but the procedure could impairment the os if it isn't done carefully. Conservators must cull between varying methods of treatment. Should they allow the object to cleft rather than apply the consolidant and only stabilize the object every bit much every bit possible? Or complete the handling, restoring the object to its original status?

Bone cleaning in progress

Treating bone, horn, and antler objects [edit]

Cleaning: Provided that objects are in proficient condition, normal surface dirt and crud may be safely removed in a variety of ways. This includes using a soft castor to lightly dust the object and dislodge dust and droppings. To remove woods droppings, and ingrown plants you can use tools such equally tweezers to carefully remove the pieces and dust off the dirt past hand.[3]

Consolidation: Consolidants are a material that can be applied to lend force to an object that is weakened. These must be applied carefully and removal of any stains or other harmful substances must exist washed first. "Consolidants may be water- or solvent-based."[iii]

- Removal of surface clay: when minimal dusting and maintenance are non successful in removing surface grit, a conservator may perform more intensive cleaning, using water and a safety cleaner.[xxx]

- Removal of soluble salts: organic materials from a salty surroundings volition invariably absorb soluble salts that will crystallize as the object dries. Common salt crystallization will cause surface flaking and may issue in irreversible damage. Conservators will remove the soluble table salt to make the object stable by using water with certain levels of chloride and ionization, only if the object is structurally sound.

- Removal of insoluble salts and stains: to remove insoluble salts and stains, conservators either use a mechanical method with picks and other tools or chemical treatment.

Drying: This is a method that can exist applied to fabric that is in off-white to excellent condition. Air-drying is the simplest method but must exist conducted carefully and monitored well, as bone, horn, antler, and ivory objects are each susceptible to fluctuations in temperature and humidity and liable to crack.[3] Air drying is the simplest method, and should exist tiresome and controlled as the risks include swelling, cracking, and delamination. Objects should be kept out of direct sunlight, away from heat sources, and in cool temperatures with low humidity levels while being dried.[3]

Dusting: A variable speed vacuum, soft, lint-free cloths, vinyl eraser crumbs, vulcanized condom sponges, and micro-attachments may be used to remove surface dust.[5] When dusting it is important to remember to apply as little pressure level as necessary. Dust can be difficult to remove without disrupting the structure of some objects, particles of debris may scratch the surface of the object. This is why it is important to ofttimes change to a make clean cloth. When vacuuming remember to avoid contact between the object, the vacuum cleaner, and its attachments. Carefully clean attachments betwixt each utilize to avoid getting dust and dirt from ane object to another.

Bug Box: Dermestid beetle larvae are a mutual pest in museum collections. They feed on a broad variety of material—particularly bird and mammal skins too equally textiles and leather.[1] Several species of Dermestes, also known as skin beetles, feed on flesh. These beetles and their larvae tin be used to your advantage. They are very constructive bone cleaners. Afterwards drying out the intended specimen simply create a "bug box," this can be any container big plenty to firm both the basic being cleaned and the dermestids doing the job. "Open-tiptop containers should be tightly covered with a screen or other material to prevent the beetles from escaping."[31]

Degreasing: Bones contain fat, this fat can exist removed using various kinds of solvents.[1] and aid mitigate pest issues also as keeping your basic in adept shape. Options include h2o-based treatments, either soaking the bone in repeated baths or simmering them in heated water, never boiling. Bones tin can too be immersed in ammonia to degrease them should fatty remain. However, i should never use detergents or other chemically based solvents every bit they "may incorporate colorants, perfumes, and other additives."[3] that could damage the objects.

Harmful conservation treatments [edit]

When addressing small-scale repairs and minimal cleaning of objects containing os, antler, or horn, there are some methods/products that are avoided.[17]

- Liquid-based cleaners or detergents used to make clean surface clay and grit tin damage the objects.

- Over-the-counter adhesives used to repair cracks and breaks can stain and become brittle over time. It is important to annotation that cracks and breaks in these organic materials can exist indicators and evidence of an object's employ and history, and therefore should not be addressed unless the health of the object is in danger.

- Wax or other protective blanket used to make repairs can obscure surface details, crusade discoloring of the surface, and are frequently impossible to remove without causing further damage.

Always consult a conservator before progressing with treatment.

Documentation [edit]

Documentation is a key piece of handling as information technology alerts future conservators to potential interactions between new and quondam treatments. This is especially of import considering no treatment is truly reversible. Documenting each progressive handling that conservators and collections staff submit an object to tin assistance to prevent any possible interactions, negative or otherwise, betwixt these materials during testing.[3] or hereafter treatments.

Co-ordinate to the ICOM Code of Ethics, "Museum collections should be documented co-ordinate to accustomed professional standards. Such documentation should include a full identification and clarification of each item, its associations, provenance, condition, treatment, and present location. Such data should be kept in a secure environment and be supported past retrieval systems providing access to the information by the museum personnel and other legitimate users."[32]

Instance studies [edit]

Wild animals - Thinktank Birmingham Science Museum - A Giant Deer

Conservation of a 19th Century Giant Deer [edit]

In 2016, conservators from the National Museum of Ireland assisted the Academy Higher Dublin Library in a conservation-restoration effort after a mishap that caused damage to the deer skull, antlers, and other skeletal elements. In addition to the immediate damage, the conservators probed the skeleton for other damage, previous repair work, any other ongoing deterioration. This case study is an overview of the steps taken in the conservation-restoration.

Investigation [edit]

When it comes to skeletal remains, they are rarely found as a complete skeleton. Information technology is common to utilize bones from many individuals to create a single mounted skeleton. An anatomical assessment was made to place and find whatever missing/wrong elements and to ensure the giant deer was anatomically right when finished.

Environmental conditions were identified and monitored to see if those had contributed to the deterioration.

Portions of previous restoration efforts were deteriorating. Farther investigation revealed a newspaper scrap used to fill up the cavities around the fe rods dated 1864, giving an approximate date the deer was mounted. The intent is to leave anything structurally sound untouched to retain as much of the historic mount as possible and minimize farther damage.

Ethical considerations [edit]

Considerations of "conservation upstanding concerns, client expectations, futurity structural stability and the limitations of the future display location"[33] must be completed earlier the intensive treatment is started.

Handling decisions [edit]

The bones were cleaned of dirt. Annihilation that appeared stable was left alone. Areas with visual plaster in fractured areas was removed with dental tools and tweezers, and incorrect paint color was removed. Radiological (X-ray) imagery was used to discover if rods were continuous through the long leg bones or if the splits along the bones were stress fractures caused past the weight of the skeleton instead of fluctuations in temperature and relative humidity causing the basic to aggrandize and contract to breaking. The antlers were permanently fastened to the skull due to their status and display location, whereas reversible measures that would be used nether unlike circumstances would not work here.

Materials and tools [edit]

Microballoon spheres and Paraloid B72 were used every bit gap filler and in the structural remodeling due to their high bulking ability while reducing the contact surface area (and further damage) to the bones, long-term stability, and like shooting fish in a barrel removal. Using the same technique throughout the restoration "limit[southward] the number of different substances introduced to the specimen and enable[south] handling to be identified equally a unmarried phase of conservation in the future."[33] Japanese tissue was used equally a barrier between the bone and the microballoon filler to increase the ease of removability in the future if needed. Copper plated mild steel welding rods, riflers, files, and wood carving chisels were used to shape skeletal element remodels, and so painted using an in-paint containing earth pigments in a Paraloid B72, IMS, and acetone solution. This solution allows for quick identification under an ultraviolet lite between the shellac-covered bone and microballoon remodel. The antlers were attached with high tension CFRP carbon fiber rods, then subconscious with modeling epoxy and in-paint and given additional support on display via heavy duty fishing line looped effectually the antlers and ceiling trusses.

Time to come care and recommendations [edit]

The temperature and relative humidity were monitored for four months. The fluctuations bespeak further damage to the bones will occur if nothing preventative is done. Currently, the giant deer skeleton's exhibition can exist no longer than six months at a time. Research is being conducted for a suitable display case with climate control so the deer may be on permanent display.

References [edit]

- ^ a b c d e National Park Service (2006). "Vertebrate Skeletons: Training and Storage" (PDF). Conserve O Gram. 11 (7).

- ^ a b c d "Care of Ivory, Bone, Horn, and Antler". Canadian Conservation Institute. Archived from the original on ii May 2016. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- ^ a b c d due east f g h "Conservation of Moisture Faunal Remains: Bone, Antler and Ivory". Canadian Conservation Establish. 14 September 2017.

- ^ Hornbeck, South. (2018). "Connecting to Collections Intendance: The intendance & documentation of ivory objects" (PDF). The Field Museum. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-05-thirteen.

- ^ a b c d e "Agents of Deterioration". Museum of Ontario Archaeology. 2014-11-21. Retrieved 2021-05-11 .

- ^ Institute, Canadian Conservation (2017-09-22). "Fire". aem . Retrieved 2021-05-11 .

- ^ Plant, Canadian Conservation (2017-09-22). "Water". aem . Retrieved 2021-05-11 .

- ^ Plant, Canadian Conservation (2017-09-22). "Thieves and vandals". aem . Retrieved 2021-05-11 .

- ^ Institute, Canadian Conservation (2017-09-22). "Pests". aem . Retrieved 2021-05-11 .

- ^ a b "Prevention – Sanitation | Museumpests.net". Retrieved 2021-05-11 .

- ^ Constitute, Canadian Conservation (2017-09-22). "Calorie-free, ultraviolet and infrared". aem . Retrieved 2021-05-xi .

- ^ Found, Canadian Conservation (2017-09-22). "Incorrect relative humidity". aem . Retrieved 2021-05-11 .

- ^ Found, Canadian Conservation (2017-09-22). "Pollutants". aem . Retrieved 2021-05-11 .

- ^ Moncrieff, Anne; Shelley, Marjorie (May 1991). "The Care and Handling of Art Objects: Practices in the Metropolitan Museum of Art". Studies in Conservation. 36 (2): 125. doi:ten.2307/1506339. ISSN 0039-3630. JSTOR 1506339.

- ^ "Managing Relative Humidity and Temperature in Museums and Galleries". Preservation Equipment Ltd . Retrieved 2021-05-11 .

- ^ a b c d e National Park Service (1993). "Preventive Conservation Recommendations For Organic Objects" (PDF). Conserve O Gram. 1 (iii).

- ^ a b c d east f thou "Bone, Antler, Ivory, and Teeth" (PDF). Minnesota Historical Guild . Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- ^ a b c d Museum Galleries Scotland. "Advice Sheet: Air Pollution" (PDF).

- ^ a b c American Museum of Natural History. "Light, Ultraviolet, and Infrared". amnh.org. American Museum of Natural History.

- ^ Parker, T. "Integrated Preventive Pest Direction" (PDF). Northeast Documentation Eye.

- ^ "Conservation of Moisture Faunal Remains: Bone, Antler, and Ivory". Canadian Conservation Institute. 14 September 2017.

- ^ Jin, J; Shipman, P (2010). "Documenting natural wear on antlers: A showtime step in identifying utilize-article of clothing on purported antler tools Author links open overlay console". Quaternary International. 211 (1–2): 91–102. doi:x.1016/j.quaint.2009.06.023.

- ^ Parker, T. "Integrated Preventive Pest Management" (PDF). Northeast Documentation Center.

- ^ a b "Bone Tools". The Smithsonian Institution's Human Origins Program. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ^ "Bone Tools". The Office of the Iowa Land Archeologist. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ^ "Use-Habiliment Analysis". Texas Beyond History. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ^ Gagne, Michael. "Dating in Archeology". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 2014-07-29. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ^ Ward, P. "The Nature of Conservation A Race Confronting Time" (PDF). The Getty Conservation Institute.

- ^ Redondo, M.R. (June 2008). "Is Minimal Intervention a Valid Guiding Principle?". E_Conservation the Online Magazine.

- ^ Hamilton, Donny. "Methods of Conserving Archaeological Material from Underwater Sites" (PDF). Centre for Maritime Archaeology and Conservation. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- ^ Sullivan, L; Romney, C. "Cleaning and Preserving Animate being Skulls" (PDF). Academy of Arizona College of Agriculture.

- ^ "ICOM Lawmaking of Ethics for Museums" (PDF). International Council of Museums.

- ^ a b Aughey, Kate (2016-01-01). "The conservation of a 19th Century giant deer display skeleton for public exhibition" (PDF). The Geological Curator. ten (5): 221–232 – via Inquiry Repository UCD.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conservation_and_restoration_of_bone,_horn,_and_antler_objects

Publicar un comentario for "Thechniques for Refinishing Plaster Framesdeer Skull and Antler Art"